Article 31 UCMJ

Rights Against Self-Incrimination for Military Members

Home » Article 31 UCMJ

Military Counsel

UCMJ Articles

Article 31 of the UCMJ – Self-Incrimination

Table of Contents

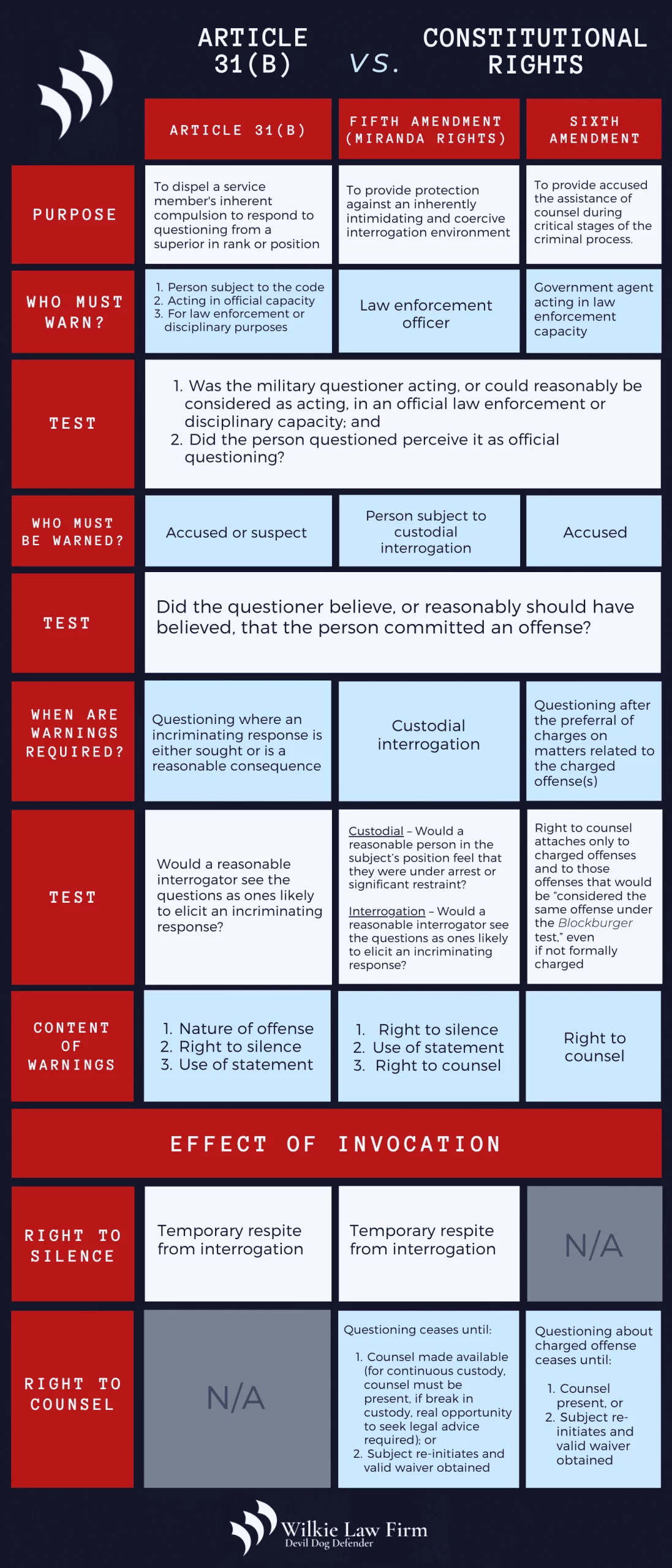

Active duty service members of the United States Military are subject to a unique set of laws called the Uniform Code of Military Justice. Within the Uniform Code of Military Justice are various articles that each focus on a different aspect of military law, as well as the corresponding punishments for violations of these laws. Some laws are unique to the armed forces, while others mimic laws and rights granted to civilian society in the United States Constitution. Article 31 of the UCMJ is one that is much like the Fifth and Sixth Amendments of the Constitution, as it covers rights against self-incrimination while serving in the U.S. Military.

North Carolina military defense attorney Aden Wilkie of the The Wilkie Law Group has decades of experience defending military personnel accused of criminal offenses. Below, he explains the details surrounding Article 31 of the UCMJ and what exactly this means for military members.

What is UCMJ Article 31?

As previously mentioned, Article 31 covers service members’ rights against self-incrimination, as well as the use of coercion, unlawful influence, or unlawful inducement in a military investigation. The text of Article 31 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice specifically states:

- No person subject to this chapter may compel any person to incriminate himself or to answer any question the answer to which may tend to incriminate him.

- No person subject to this chapter may interrogate, or request any statement from, an accused or a person suspected of an offense without first informing him of the nature of the accusation and advising him that he does not have to make any statement regarding the offense of which he is accused or suspected and that any statement made by him may be used as evidence against him in a trial by court-martial.

- No person subject to this chapter may compel any person to make a statement or produce evidence before any military tribunal if the statement or evidence is not material to the issue and may tend to degrade him.

- No statement obtained from any person in violation of this article, or through the use of coercion, unlawful influence, or unlawful inducement may be received in evidence against him in a trial by court-martial.

In 1950, Congress enacted Article 31(b) to dispel a service member’s inherent compulsion to respond to questioning from a superior in either rank or position. As a result, the protections under Article 31(b) are triggered when a suspect or an accused is questioned (for law enforcement or disciplinary purposes) by a person subject to the UCMJ who is acting in an official capacity and perceived as such by the suspect or accused.

Definitions

Before we can discuss any of this in a meaningful way, we need to establish some relevant definitions. Per Military Rule of Evidence 304 (c), a confession is “an acknowledgment of guilt.” Per the same section of the M.R.E., an admission is “a self-incriminating statement falling short of an acknowledgment of guilt, even if it was intended by its maker to be exculpatory.”

Questioning refers to any words or actions by the questioner that he or she should know are reasonably likely to elicit an incriminating response. A suspect is a person who the questioner believes, or reasonably should believe, committed an offense. An accused is a person against whom a charge has been preferred.

The collected law of Privilege Against Self-Incrimination (PASI) principles, statutes, and decisions is embodied in the MCM at Mil. R. Evid. 301, 304-305.

Article 31 vs. Constitutional Rights

Under Article 31(b), a person subject to the UCMJ who is required to give warnings¹ may not interrogate or request any statement from the accused without first informing him/her:

- of the nature of the accusation;

- that he/she has the right to remain silent; and,

- that any statement he/she does make may be used as evidence against him/her.

This may sound familiar, as it is very similar to Miranda Rights in the civilian world. However, unlike in Miranda warnings, there is no right to counsel stated.

Regardless, any consideration of the issue of “self-incrimination” relating to a member of the U.S. Military must also consider the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. These amendments set the judicial precedent when it comes to coercive confessions (or voluntariness) and one’s privilege against self-incrimination. In part, the Fifth Amendment states:

“No person […] shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself […]”

Relating to this topic, the Sixth Amendment says:

“In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right […] to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defense.”

As for the voluntariness or coercive issue, the Court will look at the totality of the circumstances. This includes whether the confession was the product of an essentially free and unconstrained choice by its maker, as well as if the accused was overborne and his capacity for self-determination was critically impaired.²

Fifth Amendment Protections in the U.S. Military (Right to Remain Silent)

While the sources of the protections differ between Article 31b and the Fifth Amendment, both focus on “testimonial compulsion.”³

The Military Appellate Courts, along with the Supreme Court, have ruled that the protections awarded under the Miranda Rights also apply to U.S. Military service members. In the civilian world, Miranda protections are triggered when a person is being subject to a custodial interrogation by official law enforcement officers. While in custody, “the subjective views harbored by either the interrogating officer or the person being questioned are irrelevant.”⁴

The operative question here is: if answered, will the questions being asked possibly result in me incriminating myself? If the answer is even potentially a yes, then invocation of your rights to remain silent should occur.

Sixth Amendment Protections in the U.S. Military (Right to Assistance of Counsel)

When you see someone invoking their right against self-incrimination on movies or in television shows, they typically only reference the Fifth Amendment and do not mention the Sixth Amendment. However, the protections under the Sixth Amendment actually cast a wider net than those granted under the Fifth.

That is, the Fifth is limited to the context of the privilege against self-incrimination, whereas the Sixth covers all that comes once the adversarial criminal justice process begins – typically at the time of preferral of charges. In addition, you don’t have to be in custody to invoke your rights under the Sixth Amendment.

The specific language of the Constitution and the statutory language of Article 31 both cover the grounds for self-incrimination, but like most other aspects of the law, the real parameters of the protection are fleshed out and defined by relevant case precedent. As you know, this is ever-changing, so it’s important that you have an experienced defense attorney who knows how to properly research and apply the law to your own factual circumstances.

What is Protected Under Article 31?

Based on a general overview of the established law, the following actions have been considered covered or protected as to the right against self-incrimination:

- Oral and written statements;

- Verbal acts;

- Physical acts which are the equivalent of speech.

As things like your mere appearance, dental impression, voice analysis, handwriting samples, and blood or urine samples are not testimonial in nature, they are not protected under this article. However, the Commander still must have good reason to seek such things from your body (e.g., probable cause determination in the form of a military equivalent to a search warrant). Of course, this is more so covered under a Fourth Amendment analysis and, as such, is beyond the scope of this discussion.

Additionally, you do not have a right to refuse to identify yourself or provide identification when requested to do so. There may be factual scenarios that would be exceptions to this general rule, but a military member refusing some of these orders may do so at their own peril, as all orders are presumed legal until proven otherwise. And yet, in some instances, being charged with the failure to obey an order may be a better position to be in as opposed to complying with the requested action and producing incriminating evidence or information.

What To Do If You’ve Been Ordered To Talk About Your Own Alleged Misconduct

As a seasoned civilian military defense attorney, Aden Wilkie gets a lot of calls from junior-enlisted service members from all branches telling him that their Chain of Command is ordering them to talk about their own alleged misconduct. That, or they order the service member to go down to the investigators and speak with them. Can they order you to report to OSI, NCIS, CID, etc.?

The answer is yes, they can order you to report. However, what they cannot do is make you talk. You must consciously choose to incriminate yourself. The best play in these situations is to not act disrespectfully, report as ordered, and then simply invoke your rights and request to have a lawyer present.

You should ALWAYS speak with an experienced attorney at the earliest possible opportunity. Only after speaking with your attorney will you be better suited to make an informed decision as to whether you want to speak to the investigator or wisely exercise your right to remain silent. It is almost never a good idea to speak with investigators at all, but certainly not without speaking with experienced legal counsel first and getting their opinion on the matter.

Self-Incrimination vs. Duty to Report

Another issue related to the topic of self-incrimination is that of rules, regulations, and orders seeking to impose on you a duty to report within a military investigation. It is important to remember that any duty to report anothers’ suspected offense, for example, does not trump your own privilege against self-incrimination. This means that if there is no way to tell authorities about alleged criminal activity without incriminating yourself, you may not be compelled to do so.

Civilian Criminal Defense Attorney for Violations of Military Law

The Military Courts have spilled plenty of ink on various factual circumstances in deciding when exactly the Article 31b warnings are required and when they are not. The answer is very factually dependent and requires the analysis and assistance of experienced military defense counsel to advise you before you make any statements. Or, if you made a statement without first being advised of your rights and properly warned, an experienced counsel can seek to suppress the statement and possibly any or all evidence arising from said statement.

So, whether you’re currently under investigation for a criminal offense or pending court-martial, seeking the help of a qualified civilian defense attorney like Aden Wilkie of The Wilkie Law Group is always in your best interest. In addition to creating a solid legal defense and protecting your rights, career, and future, Aden can also provide superior military discharge upgrade counsel, record correction, and many other military legal services. Located in Jacksonville, NC, Aden Wilkie services armed forces at Camp Lejeune and Fort Bragg as well as other bases, camps, stations, and posts across the country.

Footnotes

¹ Mil. R. Evid. 305(c)

² Culombe v. Connecticut, 367 U.S. 568, 602 (1961)

³ United States v. Williams, 23 M.J. 362, 366 (C.M.A. 1987)

⁴ Stansbury v. California, 511 U.S. 318 (1994)

Hire the Best

Please keep in mind, this article is for general information purposes only. Once an attorney-client relationship is established, you will be able to learn more about your legal options and strategies regarding your unique case. Call 910-333-9626 or complete our online submission form today for a consultation.